Victoria’s reign was the costermonger’s heyday even though the word had been coined in the early sixteenth century (coster is a corruption of costard, a kind of apple). Mayhew gave us a detailed snapshot of their lives, habits and beliefs in a series of twice weekly articles for the Morning Chronicle in the late 1840s. Later they were published as London Labour and the London Poor. Costermongers qualified because they were far from rich. Mayhew thought there were between thirty and forty thousand of them, quite a large number in a city of under two and a half million. There was no mystery about what did; they bought fruit and vegetables wholesale and sold them retail. Technically they were hawkers since only a minority had fixed stalls or standings. The rest cried out their wares as they walked the streets with barrows, donkey carts, or shallows (trays carried on the head). In the 1840s they accounted for ten percent of the cheaper produce sold in Covent Garden’s wholesale market, and a good third of Billingsgate’s fish. Earnings ranged from an average ten shillings a week to thirty at a time when a collier’s wages was around twenty.

Costermonger with Tray

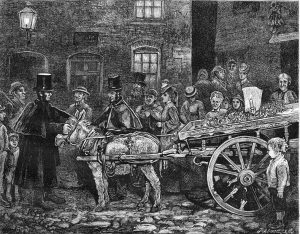

Saturday night and Sunday morning were busiest. Men were paid on Saturday evening, while Sunday’s dinner had still to be bought. Mayhew gives a very vivid account of a Saturday evening market in November.

Brightness was the first thing he noticed: naphtha flares, candles, gas jets, grease lamps, the fires of the chestnut roasters. Then the noise: hundreds of traders at hundreds of stalls calling out their wares: ‘Chestnuts, a penny a score’, ‘Three a penny, Yarmouth bloaters’, ‘Now’s your time, beautiful whelks a penny a lot’, ‘Penny a lot, fine russetts’, ‘Come and look at ’em, here’s toasters’ (that is bloaters, again).’Ho! Ho! Hi-i-i. Here’s your turnips.’ Butchers in blue aprons bellowed ‘buy, buy, buy, buy, buy’ outside their open fronted shops with gas jets wavering in the air. ‘Be in time, be in time’ barkers shouted outside the circus where the show was about to begin. Everything cheap and of use (or of no use) to the poor was there: saucepans, crockery, old shoes, trays, handkerchiefs, umbrellas, shirts. “Go to whatever corner of the Metropolis you please,” Mayhew ended, “and there is the same struggling to get a penny profit out of the poor man’s Sunday dinner.”

Three wet days in a row brought them close to starvation. The trade itself was highly seasonal and January and February were starvation months in their own right; fish was the mainstay but wholesale prices were often too high for poorer men. Weekly average takings were then only eight shillings. In March they halved. April brought roots – wallflowers and sweet-scented stocks – and takings picked up. May was a herring and wallflower month. June brought new potatoes. July came in with cherries and soft fruit. August was the time for plums and greengages when earnings peaked at thirty-six shillings. In September apples were the new best sellers but income fell sharply. October saw apples fading out and oysters coming in. In November the Lord Mayor allowed sprats to be sold (he had the power to do so, presumably, because he controlled Billingsgate, otherwise his writ ended at the City walls.) Business was poor in early December but flared up briefly at Christmas with holly, ivy, and oranges, and then the dead new year began again.

There were thirty-two big street markets in London where costers lived together in colonies in courtyards and alleyways. Home for a family was almost invariably a single small room. Mayhew visited three.

The first were what he called thriving costers — mother, son and daughter. Unsurprisingly they were teetotal. Pictures of saints were pasted on the wall above the fireplace. Crockery busts of Prince Albert and M. Jullien stood on the mantelpiece. They had a bedstead with a quilt and a dresser for cups and blue plates (clean, Mayhew pointed out).The floor was scrubbed not just clean but white. A pot of stew bubbled on the fire.

Five people lived in the next room he visited. He called it a kitchen though it sounds more like a cellar. A barrow, parked outside the window, darkened the room. The railings rattled so loudly when pedestrians walked by that people inside had to stop talking. There was only one bed. Where did they sleep? He wondered but never asked. A cat sat on the hearth. “They keeps the varmint away,” said the woman, “and gives a look of home.”

Lastly he visited three women living together in a single room on the first floor of a house with a slanting roof. The room was so filled with smoke he could barely see the cups in a three cornered cupboard only feet away. They had no bed, only a straw mattress on the floor. A young woman lay there. She’d just given birth. The child was dead. Among the bonnets was a clean night cap, for when the doctor called. The room was nine feet square and immediately below the roof; between the laths where the tiles were missing you could

see the sky. Still: “We never want for water for we can catch plenty just over the chimney place,” the old woman told him jokingly. Window panes were brown paper. Mats, normally unheard of, were needed to stop things falling through gaps in the floor into the stable below. But, as the old woman explained, the chimney smoked only when the wind was in the wrong direction and the rent was nine pence a week. So: “Mustn’t grumble,” she said, uttering the exact mantra English people would use for the next hundred or so years whenever things were not too good, or very often.

Yet costers lived most of their lives on the streets; breakfast might be bread and butter at a coffee stall, lunch a pie from a passing pieman or meat bought in a butcher’s but cooked in a tap-room’s oven. Beer shops, however were their natural haunts; nearly four hundred of them, Mayhew claimed, relied entirely on their trade. Typically a coster spent half his earnings on beer. But beer shops also provided him with recreation. Gambling was endemic. They’d bet their stock money, for example, against a pieman’s tray of pies as they waited for the wholesale markets to open. Mostly they gambled in the beer shops — cards, three up (a game played by tossing three coins up in the air). They boxed (said they were better boxers than any but professional prize-fighters) for beer and side bets. Bouts were short since the winner was the man who first drew blood. Dog fights in beer shops were also common, and illegal. Ratting was popular, as was pigeon keeping, though perhaps not as popular as pigeon shooting. Not that the costers shot. They picked up injured birds when they fluttered down outside the wall of the Battersea shooting ground. They fetched three pence apiece.

Taken from: http://www.victorianweb.org/history/work/costermonger/index.html

Mayhew, Henry. London Labour and the London Poor. Vol 1, 1851