Police in Victorian England

The Metropolitan Police commonly known informally as the Met, Scotland Yard or “the Yard”, is the territorial police force responsible for law enforcement in the London boroughs. The Met does not include the “square mile” of the City of London, which is policed by the much smaller City of London Police.

The Metropolitan Police Service, whose officers became affectionately known as “bobbies”, was founded in 1829 by Sir Robert Peel under the Metropolitan Police Act of 1829 and on 29 September of that year, the first constables of the service appeared on the streets of London. In 1839, the Marine Police Force, which had been formed in 1798, was amalgamated into the Metropolitan Police. In 1837, it also incorporated with the Bow Street Horse Patrol that had been organized in 1805.

In 1842 taking over a function formerly the responsibility of the Runners, a new investigative force was formed as the “Detective Branch”. And first consisted of; two Inspectors, six Sergeants and a number of Constables.

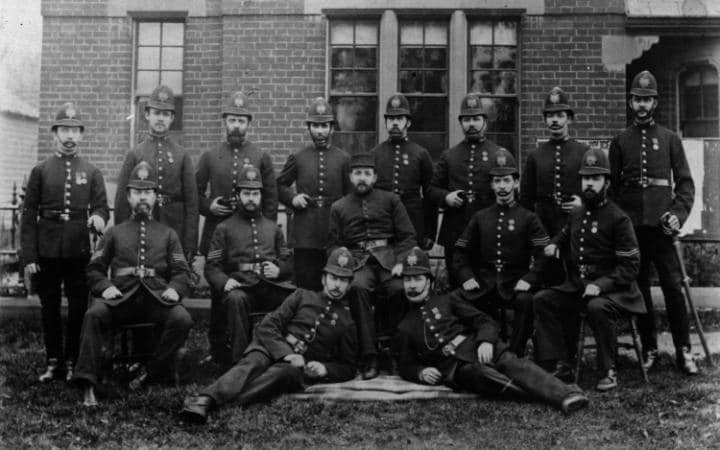

From 1829, to 1839, Metropolitan Police officers wore blue swallow tail coats with high collars to counter garroting. This was worn with white trousers in summer, and a cane-reinforced top hat, which could be used as a step to climb or see over walls. In the early years of the Metropolitan Police, equipment was little more than a rattle to call for assistance, a single edged sword, a wooden truncheon and (in some cases) flintlock pistols. As the years progressed, the rattle was replaced with the whistle, swords were removed from service, and flintlock pistols were removed in favour of revolvers. Initially, police constables were required to wear their uniforms at all times, whether they were on duty or not. A cloth brassard or arm band, with black and white vertical stripes, known as a “duty band”, was worn on the left forearm while on duty and removed at the end of the shift. In an emergency, duty bands could also be issued as the sole item of uniform if large numbers of special constables were required. The City of London Police are the last force to retain the duty band.

In 1863, the Metropolitan Police replaced the tailcoat with a tunic, still high-collared, and the top hat with the custodian helmet, which is based on the Pickelhaube. With a few exceptions (including the City of London Police, West Mercia Police, Hampshire Constabulary and States of Guernsey Police Service), most forces helmet plates carry a Brunswick star. The helmet itself is of cork faced with fabric. The design varied slightly between forces. Some used the style by the Metropolitan Police, topped with a boss, while others had a helmet that incorporated a ridge or crest terminating above the badge, or a short spike, sometimes topped with a ball. Luton Borough Police (1876-1947) wore a straw helmet in a similar style to the Bermudan police helmet, with a small oval plate.

Scotland Yard

The name derives from the location of the original Metropolitan Police headquarters at 4 Whitehall Place, which had a rear entrance on a street called Great Scotland Yard. The Scotland Yard entrance became the public entrance to the police station, and over time the street and the Metropolitan Police became synonymous. By 1887, the Metropolitan Police headquarters had expanded from 4 Whitehall Place into several neighbouring addresses, including 3, 5, 21 and 22 Whitehall Place; 8 and 9 Great Scotland Yard, and several stables

In 1888, during the construction of the new building, workers discovered the dismembered torso of a female; the case, known as the ‘Whitehall Mystery’, was never solved. The force moved from Great Scotland Yard in 1890, to the newly completed building on the Victoria Embankment, and the name “New Scotland Yard” was adopted for the new headquarters.

Wages

The original standard wage for a Constable was one guinea (£1.05) a week. Recruitment criteria required applicants to be under the age of 35, in good health, and to be at least 5 ft 7 in (1.70 m). Working shifts lasted 12 hours, 6 days a week, with Sunday as a rest day. Metropolitan Police officers do not receive a boot allowance.

Woman Police Officers

The official employment of the first woman by the Metropolitan Police dates back to May 1883. Her task was to guard female convicts and women under police supervision. The second woman was appointed in September 1886. In March 1889, fourteen women were employed as “police matrons” to supervise women and children in court. Then the number of women employed by the police all over the country slowly increased during the following years.

Policemen and Firearms

The force did not routinely carry firearms, although Sir Robert Peel authorised the Commissioner to purchase fifty flintlock pocket pistols for use in exceptional circumstances, such as those which involved the use of firearms. Later, the obsolete flintlocks were decommissioned from service, superseded by early revolvers. At the time, burglary (or “house breaking” as it was then called) was a common problem for police. “House breakers” were usually armed. It was then also legal (under the Bill of Rights 1689) for members of the public who were Protestants, as most were, to own and use firearms. Following the deaths of officers by firearms on the outer districts of the metropolis, and public debate on arming the force, the Commissioner applied to Robert Peel for authorisation to supply officers on the outer districts with revolvers. The authorisation was issued on the condition that revolvers would only be issued if, in the opinion of the senior officer, the officer could be trusted to use it safely and with discretion. From then, officers could be armed.

During the 1860s, the flintlock pistols that had been purchased in 1829 were decommissioned from service, being superseded by 622 Beaumont–Adams revolvers firing the .450 cartridge which were loaned from the army stores at the Tower of London following the Clerkenwell bombing. In 1883, a ballot was carried out to gather information on officers’ views on whether they wished to be armed, and 4,430 out of 6,325 officers serving on outer divisions requested to be issued with revolvers. The now obsolete Adams revolver was returned to stores for emergencies, and the Bulldog ‘Metropolitan Police’ revolver was issued to officers on the outer districts who felt the need to be armed. On the night of 18 February 1887 PC 52206 Henry Owen became the first officer to fire a revolver while on duty, doing so after he was unable to alert the owners of premises on fire.

British Bull Dog

The British Bull Dog was a popular type of solid-frame pocket revolver introduced by Philip Webley & Son of Birmingham, England in 1872 and subsequently copied by gunmakers in Continental Europe and the United States. It featured a 2.5-inch (64 mm) barrel and was chambered for .44 Short Rimfire, .442 Webley, or .450 Adams cartridges, with a five-round cylinder. double-action revolver with a swing-out ejector rod and a short grip Intended to be carried in a coat pocket

Equipment

From the Metropolitan Police’s foundation, the force had relied on the use of hand rattles for officers to signal the need for assistance. In 1884 the Home Secretary invited competition from many companies to invent a “police whistle” to replace the rattle. J.Hudson & Company of Birmingham were awarded the contract for 7,175 whistles at the price of 11d each. At the same time, a competition for the contract to supply the Metropolitan Police with new truncheons was under way. This contract was won by Ross & Company, who supplied the Metropolitan Police with Lignum vitae truncheons. In 1886, during a riot between warring working parties in Hyde Park, many truncheons were damaged or broken, samples were sent off to be tested by the Royal Army Clothing Department, at a cost of 16 shillings per day. In October 1886, 900 pounds worth of Lance and Crocus wood were purchased, to use in place of Lignum vitae that was deemed unsuitable after Army testing.

The truncheon also acts as the policeman’s ‘Warrant Card’ as the Royal Crest attached to it indicated the policeman’s authority. This was always removed when the equipment left official service (often with the person who used it).

Rattles and Whistles

When Sir Robert Peel formed the London Metropolitan Police Force in 1829, part of each Bobby’s kit was his rattle.

The origin of the rattle is not clear, but what has come to be known as the “Victorian Police Rattle” came into use sometime in the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century when night watchmen and/or village constables began using them to “raise the alarm”. They proved to be an ideal method to summon aid, sound the fire alarm, or, just generally get folks attention. A traditional rattle was constructed of wood, usually oak, where one or two blades are held in a frame and a ratchet turned – generally by swinging – to make the blades ‘snap’ thus creating a very loud noise.

The police rattles were made to be as loud as possible, as they were used to call for help or alert the neighborhood to trouble. They were large, about the size of a shoe, and made to fold up and fit into tailored pockets in one of the swallow-tails of their tailcoats (the other tail contained their truncheon). They were also weighted with lead, providing both extra weight to aid in strong rotation, and to allow them be used as a club if necessary.

The police rattle was replaced by the simpler, lighter, and louder police whistle in the 1880s. Rattles didn’t die out entirely, as they were also used by private security guards, and fire brigades.

In 1883 the Metropolitan Police conducted tests and found that the sound from a whistle, already being used in some provincial forces, could be heard at 1000 yards – almost twice the effective distance of a rattle. Not only that, but the rattles were somewhat cumbersome, awkward to operate and prone to rot/warping. Constables were often subject to attacks from their own rattles. In 1884 whistles were issued in place of rattles and by 1887 all rattles had been withdrawn from use by the Met.

Signals, Whistle and Tap

If a sergeant had gone over an officer’s beat and was unable to find him, he would then go to its center and each extremity and tap his nightstick twice. This was known as a “call rap.” The officer would answer in like manner. If the visiting supervisor required the presence of the officer, he would give a single rap. In lieu of the nightstick, a whistle could be used.

If an officer on his beat required the presence of another officer on an adjoining beat, he would, in ordinary cases, give a single rap or whistle, which would be answered in like manner. Then the officer making the call would again give a single rap or whistle in answer. In case of fire, riot or other emergency, he would give three taps or whistles in quick succession and all officers hearing it would answer by a single rap or whistle and immediately come to the assistance of the officer making the call. If an officer was in pursuit of a person at night, he was, from time to time, to give a single rap or whistle to inform other officers of his route. So that when a disturbance occurs… “If he is opposed in the performance of his duty, he shall blow his whistle, and the policemen who hear it shall answer the same by forthwith proceeding to his assistance.”

Stations and Divisions

Between 1829 and 1886 local divisions each with its own police station were established, each lettered A to Y allocating each London borough with a designated letter. These divisions were:

A (Westminster);

B (Chelsea);

C (Mayfair and Soho);

D (Marylebone);

E (Holborn);

F (Kensington);

G (Kings Cross);

H (Stepney);

K (West Ham);

L (Lambeth);

M (Southwark);

N (Islington);

P (Peckham);

R (Greenwich);

S (Hampstead);

T (Hammersmith)

V (Wandsworth)

W (Clapham);

X (Willesden) and

Y (Tottenham);

J Division (Bethnal Green)

Most police stations can easily be identified from one or more blue lamps located outside the entrance, which were introduced in 1861

One of the first cases investigated by the newly formed Detective Branch was The Bermondsey Horror of 1849, in which a married couple, Frederick and Marie Manning, murdered Patrick O’Connor and buried his body under the kitchen floor. After going on the run they were tracked down by Detective Sergeants Thornton and Langley and publicly hanged outside Horsemonger Gaol in Southwark.

After Rowan’s death in 1852, Mayne presided as sole Commissioner. In 1857 he was paid a salary of £1,883 (a fortune, roughly equivalent to £1.2m in 2009), and his two Assistant Commissioners were paid salaries £800 each, approximately £526,000 in 2009.

It took some time to establish the standards of discipline expected today from a police force. In 1863, 215 officers were arrested for being intoxicated while on duty. In 1872 there was a police strike, and during 1877 three high ranking detectives were tried for corruption at the Old Bailey. Due to this latter scandal the Detective Branch was re-organised in 1878 by C. E. Howard Vincent, and renamed the Criminal Investigation Department (CID). This was separated from the uniformed branch and its head had direct access to the Home Secretary, by-passing the Commissioner.

The threat of Irish terrorism was combated by the formation of the Special Irish Branch, in March 1883. The “Irish” sobriquet was dropped in 1888 as the department remit was extended to cover other threats, and became known simply as Special Branch.

Important criminal investigations of the period included the Whitechapel murders (1888) and the Cleveland Street scandal (1889)