Getting about London and the Countryside…

Hackneys, Hansom Cabs and Coaches

In cities of any size, there are a number of 2-and 4-wheeled, horse-drawn coaches available for hire; either roaming through the streets or waiting in neat queues at cabstands. There are several common types:

The Hackney Cabs or coaches are a hireable vehicle with specifically four wheels, two horses and six seats, and are driven by a Jarvey (a man whose business it is to drive a coach or carriage, a horse-drawn vehicle designed for the conveyance of passengers.) Usually these are used or retired private coaches where the arms and insignia are painted over.

Many of these have widely replaced by lighter and more maneuverable Cabriolets. A cabriolet is a light horse-drawn vehicle, with two wheels and a single horse. The carriage has a folding hood that can cover its two occupants, one of whom is the driver. It has a large rigid apron, upward-curving shafts, and usually a rear platform between the C springs for a groom. The design was developed in France in the eighteenth century and quickly replaced the heavier hackney carriage as the vehicle for hire of choice in Paris and London. The ‘cab’ of taxi-cab or “hansom cab” is a shortening of cabriolet

The Hansom Cab

Originally called the Hansom safety cab, it is designed to combine speed with safety, with a low center of gravity for safe cornering. Hansom’s original design has been modified by John Chapman and several others to improve its practicability, but retain Hansom’s name.

Originally it was for one passenger protected by a high hood which separated them from the driver at his side and had a square body in a square frame with wheels as high as the vehicle. It has evolved to carry two passengers (three if squeezed in) and a driver who sat on a sprung seat behind the vehicle. The passengers could give their instructions to the driver through a trap door near the rear of the roof. They could pay the driver through this hatch and he would then operate a lever to release the doors so they could alight. In some cabs, the driver could operate a device that balanced the cab and reduced strain on the horse. The passengers are protected from the elements by the cab, and by folding wooden doors that encloses their feet and legs, protecting their clothes from splashing mud. Later versions also have an up-and-over glass window above the doors to complete the enclosure of the passengers. Additionally, a curved fender mounted forward of the doors protects passengers from the stones thrown up by the hooves of the horse.

The Hansom, a 2-wheeled, enclosed cab that would comfortably seat 2

The Brougham

A Brougham (pronounced “broom” or “brohm”) is a light, four-wheeled horse-drawn carriage. It is named after the politician and jurist Lord Brougham. It has an enclosed body with two doors, like the rear section of a coach; it sat two, sometimes with extra pair of fold-away seats in the front corners, and with a box seat in front for the driver and a footman or passenger. Unlike a coach, the brougham has a glazed front window, so that the occupants could see forward and are still protected from weather and road dirt. The forewheels are capable of turning sharply. A variant, called a brougham-landaulet, has a top collapsible from the rear doors backward.

The Brougham, a 4-wheel enclosed coach that could seat 2 or 4.

The Clarence “Growler”

The Clarence or ‘Growler’ is a closed, four-wheeled vehicle with a projecting glass front and seats for four passengers inside. The driver sat at the front, outside the carriage. Often second-hand Clarences came to be used as hackney carriages, earning the nickname ‘growler’ from the sound they made on London’s cobbled streets.

The following fares were typical of London in the second half of the century:

For fares that start and finish in a 4 mile radius around the Charing Cross station – 1/0 for the first two miles, and 0/6 for each mile or part of a mile.

Each mile beyond 4 miles of Charing Cross – 1/0 Each person beyond 2 – 0/6 (each child under the age of 10 counted as half a fare.)

A reasonable amount of baggage could be carried inside the cab; for each parcel carried on the outside – 0/2

A cab could be asked to wait – the first 15 minutes was free, but every 15 minutes or portion thereafter was 0/6 for a 4-wheeled coach, or 0/8 for a 2-wheeled cab.

Drivers were not obligated to travel more than 4 miles per hour – if asked to rush, he was entitled to an extra 0/6 per mile.

Drivers had the right to refuse any fares in excess of 6 miles, at their discretion.

Fares were to be agreed upon in advance. If a driver agreed to a lesser fee, and then required a larger fee at the completion, there was a 40s fine. In the event of a dispute, drivers were required, if requested, to take the passenger to the nearest police-court or police station for the local magistrate to decide the matter.

Lost luggage was required to be turned in to the nearest police station within 24 hours (if not claimed sooner.) Anyone claiming the luggage was required to prove to the satisfaction of the local police commissioner that it was his or her property, pay all expenses, and a suitable reward to the cab driver as determined by the commissioner.

It was not considered proper for a woman to accompany a man in a Hansom cab. An open Landau was more suitable.

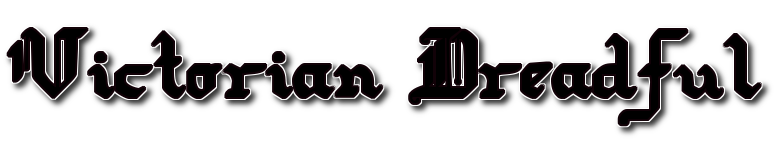

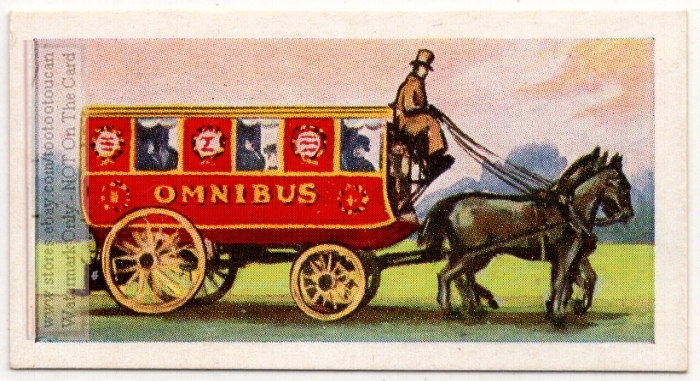

The Omnibus

A horse-bus or horse-drawn omnibus was a large, enclosed, and sprung horse-drawn vehicle used for passenger transport before the introduction of motor vehicles. It was mainly used in both the United States and Europe, and was one of the most common means of transportation in cities. In a typical arrangement, two wooden benches along the sides of the passenger cabin held several sitting passengers facing each other. The driver sat on a separate, front-facing bench, typically in an elevated position outside the passengers’ enclosed cabin. In the main age of horse buses, many of them were double-decker buses. On the upper deck, which was uncovered, the longitudinal benches were arranged back to back.

Similar, if smaller, vehicles were often maintained at country houses (and by some hotels and railway companies) to convey servants and luggage to and from the railway station. Especially popular around 1870–1900, these vehicles were known as a ‘private omnibuses’ or ‘station buses’; coachman-driven, they would usually accommodate four to six passengers inside, with room for luggage (and sometimes additional seating) on the roof.

Wagonette

A small open wagon with or without a top, but with an arrangement of the seats similar to horse-drawn omnibuses, was called a wagonette.

Long-Distance Coaches (Stagecoaches)

The Concord Coach was widely used in America and Europe; it weighed about 3,000 lbs. empty and could carry over 2 tons of passengers and cargo when pulled by 6 or 8 horses. The body of the coach hung from a system of leather straps, transforming much of the bumps and vibration of the road into a gentle rocking motion. One difference between the European version of the Concord and its American cousin is that in the former, the driver’s seat is attached to the chassis, rather than the cab, so the driver would have to suffer through everything the road had to offer. On both sides of the Atlantic, the driver sat on the right, while the guard (riding “shotgun”) sat on the left.

Inside the cab, there were three bench seats – two facing forward, and the front most facing back – there was storage space beneath the benches, which sat three comfortably. Three more could sit on a bench on the roof with their legs hanging off the back (where they had a ringside view of anyone or anything pursuing the coach.) It could carry 12 persons comfortably, but twice that number could be crammed inside in a pinch.

Despite the ‘gentle’ suspension, a rough road could frequently toss riders off of the top seats, and on the less-developed American roads, even overturn the coach – something that happened often enough that most travelers resigned themselves to enduring at least one rollover on their journey.

A coach could travel about 35 miles in 8 hours. Some stage lines would run around the clock – only stopping long enough to change horses or drivers; others would only run during the daytime, stopping at stations for an overpriced meal and a bedbug-ridden cot for the night. On the better-quality roads back east or in Europe, coaches could travel up to 9 or 10 miles per hour for stretches. It typically took an entire month to cross the United States from coast to coast.

When mud or winter snows made a stretch of road impassible, the driver would send ahead to a station to send a “mud wagon”, a lighter, 4-horse coach that would ferry the passengers and cargo across the bog. Fares were about $0.08 or 1 groat per mile.

In the Countryside

Farm Wagons

Almost every farm has a Farm Wagon for hauling produce, hay and assorted materials. The Heavy Farm Wagons are essentially the same as the Freight Wagons found in town as well as in the countryside. These require a team of four large horses, or as found on some farms, oxen. Lighter freight and farm wagons can usually be drawn by two horses. The American one or two horse light wagon, the ‘Buckboard’ is not as common in Britain.

The Dog Cart

A dogcart (or dog-cart) is a light horse-drawn vehicle, originally designed for sporting shooters, with a box behind the driver’s seat to contain one or more retriever dogs. The dog box could be converted to a second seat. Later variants included : A one-horse carriage, usually two-wheeled and high, with two transverse seats set back to back. It was known as a “bounder” in British slang (not to be confused with the cabriolet of the same name). Two horse teams are sometimes used for longer excursions.

Some four wheeled versions do not require the dog box to be removed.

The Trap

The Pony Trap, or Horse Trap, or simply a Trap, is a light, often sporty, two-wheeled or sometimes four-wheeled horse- or pony-drawn carriage, usually accommodating two to four persons in various seating arrangements, such as face-to-face or back-to-back.

Personal Carriages

In addition to the common Traps and carts, there are a variety of carriages used by the Upper Classes for travel. Most are intended for relatively short jaunts and day trips with larger private coaches used for longer travel or, more commonly, longer trips are made by rail. These are general examples of the selection available, wealthy individuals often had custom carriages made to accommodate their particular needs.

The Victoria

The Victoria is an elegant carriage style of French origin, possibly based on a phaeton made for George IV. A victoria may be visualized as essentially a phaeton or brougham with the addition of a coachman’s box-seat, but not enclosed and therefore open to the elements.

Though in English the name ‘victoria’ was not employed for a carriage before 1870, when one was imported to England by Edward VII, then Prince of Wales, in 1869, the type was made some time before 1844. In 1845 the renowned de Rosemont sisters Olympe, Rosalie, Lydia and Laureline de Rosemont, who were well known for championing new vehicles, machines and fashions, purchased one. It was very popular amongst wealthy families. Diarist Lady Leonora Elmtree-Gray writes about her friend getting one made. She says it “is a vehicle of delightful elegance and delicacy.” On a low body, it had one forward-facing seat for two passengers and a raised driver’s seat supported by an iron frame, all beneath a calash top. It was usually drawn by one or two horses. This type of carriage became fashionable with ladies for riding in the park, especially with a stylish coachman installed. It was particularly smart to have a pair of coachmen who ‘matched’ – of similar height and colouring, etc. Elisabetha Orpington-Plumrose appeared in popular the magazine ‘Town Tit-Bits’ for having her victoria driven by identical twins.

Phaeton

A phaeton (also phaéton) was a form of sporty open carriage drawn by one or two horses. A phaeton typically featured a minimal very lightly sprung body atop four extravagantly large wheels. With open seating, it was both fast and dangerous, giving rise to its name, drawn from the mythical Phaëthon, son of Helios, who nearly set the Earth on fire while attempting to drive the chariot of the Sun.